76 – James Morrison Hamilton was born on the 4th of November 1896 in Mildura, Victoria, to parents James Alexander and Barbara Farquhar (nee Smith). James also had an older sister, Margaret Daisy. When James enlisted in the 1st FCE, he was already serving in the citizens’ militia with the 73rd infantry in Victoria. He was also working as a carpenter and was described as a big strapping lad, a 6-footer, which for the time was considered very tall.

After embarking from Sydney on the troop ship A19 AFRIC on the 18th October 1914, James Hamilton and the majority of the original contingent of the 1st Field Company arrived at Alexandria, Egypt on the 5th of December 1914. Commanding Officer Major John McCall and fourteen engineers, together with fifty-six horses, arrived on the A6 ‘Clan Macquordale’, and the 1st FCE reinforcements arrived on the A35 ‘Berrima’, adding to the full complement of 228 members of the 1st FCE.

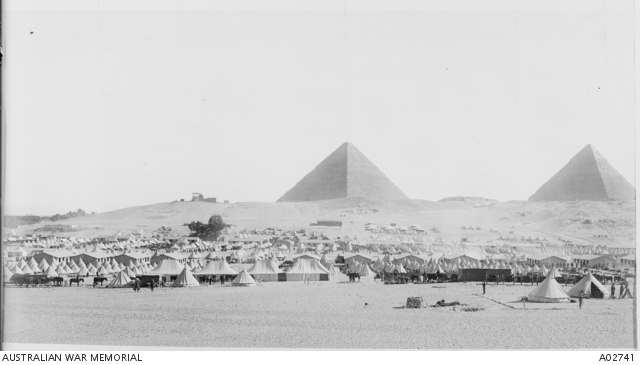

Within days the small company of men entrained for Alexandria and arrived on the 9th of December at Mena Camp, 10 miles from the centre of Cairo and only a short distance from the great pyramids of Gizeh. They would spend nearly three months mastering camp life in the desert, fine-tuning their bridgebuilding skills, constructing pontoons, digging wells and laying water pipes and maintaining all the regular military drills.

In February, 151 Ernest Murray gave his account of the sappers’ progress at Mena Camp.

“February has been a busy month with all branches of the Forces at Mena & elsewhere in Egypt. There has been all kinds of speculation & opinion as to where we would go & when. During the month the Engineers have been very busy training at Field work & during that time we have been supplied with Pontoons & have done a good deal of Bridging with them & have got on very well”. – February 1915 – from the Diary of 151 Ernest Murray

On the 28th Feb 1915 the men of the 1st FCE left Mena Camp and the mystery of the great Pyramids and entrained to Alexandria. On the 2nd March embarked on the troopships ‘Suffolk’ and ‘Devanha’ for Lemnos Island.

In a letter to his parents, James briefly explained that he was leaving Egypt and possibly heading for Turkey.

“We engineers had been out putting a bridge across one of the canals, and when we got back to camp the O.C. told us that we were to be attached to the 3rd Brigade of Infantry and move off with them in five days.

I can tell you there was a bit of excitement running round. We were kept pretty busy in packing up our goods and getting our wagons fixed and by Sunday, 28th February, we were ready to move; no one knew where we were going, but the most popular rumour had it that we were off to Turkey; anyway, about 5.30 p.m. we swung out of Sapper Lane into Canberra Road, mid the cheers of the other troops that were left behind, gave a salute to General Bridges at Divisional Headquarters, took a last glimpse at the Pyramids and turned into the Cairo road and settled down for a 10 mile march into the station. We were a gay party and every song from “Onward Christian Soldiers” down to “Tipperary” had its turn. We arrived at the station about 1.30 p.m. and started to load our wagons and horses on the train”.

“March 1st, we said goodbye to Cairo and tried to get to sleep. At 7 a.m. we arrived at Alexandria and embarked on the S.S. Suffolk, which sailed next day at 12 o’clock. When we had been going about 3 hours, we were told that Lemnos Island was our destination and that we were to make an intermediate base camp and hospital.

We were 2½ days on the journey and land was in sight most of the way, as we had to pass through the Grecian Archi(wheelbarrow). You’ll be able to see Lemnos Island marked on the map; it’s just before you turn round the corner into the Dardanelles.

We sighted it early on the third day and at 7 a.m. we were just outside the heads -you can’t see the harbor until you get right through the heads. When we got in, we saw about 20 warships (some coaling, others ready to move out) and we got a cheer from the sailors from the nearest boats.

We afterwards found out from the sailors that the harbor was a base for the naval people as well. There was one transport in when we arrived, and the rest of the brigade began to turn up during the next few days.

There was plenty of work to be done for we engineers, so we soon got a start on; one section was ashore on the water supply, digging wells and laying pipes, another was on shore building a pier and making a road up to the camp. Our section had to stay on board and look after stores and timber. Another section was a sort of reserve, and they were needed too for about a week later they had to go and put-up beacons around the harbor for the transports to line up on.

About this time a lot of British transports came in with the R.M.L.S. and some Naval Brigade men. These men were the ones that were sent to the relief of Antwerp and many a tale they told us about that great fight over there. All the boats with them went out of the harbour again, and later we learnt that they went to Port Said.

About 6 weeks after we went to Lemnos, the rest of the Australian Division began to come in, so we began to look forward to some fun, as the sailors off the battleship said that they thought the troops were going to be landed at the Dardanelles soon. About April 20th there were about 175 transports, 35 battleships, 5 submarines and about 20 destroyers in the harbor It was a great sight, I can tell you.

Then rumour got round that we were off soon, and it seemed so too, as we were supplied with ammunition, iron ration and 3 days’ field rations; and then we practised landing on the shore. The way we were to do it was to get down rope ladders from the transport into a destroyer, which took us as near to the shore as possible; then we got into row boats and were towed in further by the pinnaces and when they let go we had to row right in and duck for cover.

We practised this for a couple of times and then on the 24th, Saturday, we made a move to take up our position at the head of the line as we, with the 3rd Brigade, had the honour of being the landing party for the whole of the division (and we didn’t kid ourselves either).

We got a move on at 4 p.m. and at 8 o’clock our transport stopped and we began to get into the destroyer. We had about 15 miles yet to go and as we were to make the landing in the early morning, they didn’t move off for a while.

We had hot cocoa served out to us on the destroyer and then sat down to yarn to the sailors; you’d think we were on a picnic, but many a time our thoughts went back to dear old Australia and my mind seemed to see you looking up at my photo. I knew what you’d expect, and I vowed to myself I’d do my best.”

On the 24th April 1915, the 1st FCE was split up among the Infantry to form the first wave of men to land on the shores of Gallipoli on the morning of the 25th April 1915. Known as the ‘covering force’. their task was to storm the beach and then push inland as fast and as far as possible.

The first wave included units of the 3rd Australian Brigade consisting of the 9th (Queensland), 10th (South Australia), 11th (Western Australia) and 12th (Tasmania, with some South Australia and Western Australia) Battalions and the 3rd Field Ambulance and members of the 1st Field Company Engineers, the only company representing New South Wales.

The company left Lemnos at 2pm in the afternoon on the HMS Prince of Wales, London and Queen. The Drivers, wagons and horses went onboard the transport ship Nizam, and one section was sent to the Ionian, Mald and Suffolk. Most felt honoured to be among the first to land at Gallipoli, but their excitement for adventure was short-lived as many would become casualties.

Many of the sappers like James were part of the second wave, transported by seven destroyer class warships, (the HMS Beagle, HMS Colne, HMS Foxhound, HMS Scourge, HMS Chelmer, HMS Usk and the HMS Ribble ). In a similar offshore position as the first wave, they were then dropped off into the destroyers’ lifeboats. Those from the HMS Ribble were towed by a steam pinnace, within 50 yards of the shore and those from the other six destroyers had to row the whole way into a hail of bullets.

James, on board the HMS Usk, gave his account of the events on the 25th April 1915.

“At 12.30 we got a move on again and the destroyer (the ‘Usk’ is its name) plowed through the water and rolled about a treat (they do roll some when they get going). About 3.30 we slowed down and were told we were getting near. We could see the Turkish searchlights flashing away over on the Dardanelles, looking for the mine sweepers, which always work at night. The night was lovely, clear and pretty cool; the moon was shining, and you couldn’t hear a sound bar the swish of the waves against the side of the boat.

The destroyer stopped and we could plainly see the shore, with big hills running up from it. We just began to get into the row boats, when crack and the Turks started shooting; but they were precious bad shots and they all went wide except a few, which came unpleasantly close; poor Dorky Burton (you’ll see his photo on that one I sent) got one in the leg before he got off the destroyer; he swore and asked our Corporal to “stick a damned Turk” for him.

Then our boat was picked up by a picket boat and towed as close as possible to the shore. We then had to row for it, the bullets whistling around us; but no one was hit. The boat grounded in five feet of water, and we had to-jump for it-up to the neck in water. We waded ashore and ducked for cover. The other boats didn’t get off so easily as we did. Two of our chaps were shot dead before they could get cover; they were B. Freebairn and C. Page, two of the nicest fellows one could meet. Another of our chaps, M Cummings, was shot through the ankle.

We could do nothing but lie still behind cover until the whole brigade had landed, which wasn’t long, and then came the order: “Fix Bayonets,” and then someone shouted: ” What about Australia now.” With a yell and cheer we charged up the hill, and if it hadn’t been so tragic it would have been funny. The Turks turned and ran; we chased them ‘down the other side and up another hill. In some places we had to leg each other up; then we were on again. If a big fat Turk dropped behind we raced each other to see who was going to have first prod. We were completely mad for a time.

We stopped on the second hill because we could go no further; we were knocked out completely. Some dug themselves in, as the Turks’ big guns were firing on them, and my word that shrapnel is cruel; the rifles and machine guns are a mere detail, but the shrapnel-Anyway, we held our position on the second hill. All the engineers were called back from the firing line, as we had plenty of work to do elsewhere. We had to make roads up the side of the hill for the stretcher-bearers and transport carriers; we had to dig gun pits for our big guns and look after the water supply, fix up communication trenches and overhead cover, barbwire entanglements and many other jobs.

Our section seemed to catch most of the casualties. Another man was killed on the first Sunday; that made 3 killed, 2 wounded, 3 missing. One of the missing turned up two days later.”

Fifteen days later, James was wounded in action on the 9th May at Gallipoli, a bullet wound to his left arm and the finger of his right hand, and he was transferred to Lemnos and then Cairo to convalesce.

The following is an extract from a letter James had mother written from his hospital bed in Kars-el-Aini Hospital, Cairo, to his mother on the 14th May, shortly after he was wounded at Gallipoli.

“On Wednesday, the 28th. a bit of shrapnel hit me, a smack on the chin and landed about two yards away in a rock; it just took the skin off my chin, but if I had it another inch forward, I wouldn’t have one now. Anyway, it was close enough to me.

On Sunday, 2nd May, I lost my best chum, Cecil Howlett. Our section was going up the ” Valley of Death ” (as they call it) when we stopped for a spell. We had been down about five minutes when a shell whizzed in amongst us. It’s a blessing for the section that it didn’t burst, but the shell hit poor Cecil on the head and killed him instantly, and the cap of the shell hit Tommy Drane on the knee and took the kneecap right off; it cut us up more than the whole week of hard work and strain.

I was one of the burial party, although I didn’t want to go, but our Lieutenant said we had to get used to it. I had to bite my lip to stop the tears coming, and nearly everyone was the same. He was such a big, kindly fellow-boyish in some things and a man in others. I sort of felt I didn’t care a hang what happened to me after that.

It was Wednesday, 5th May, that I stopped one. It was a sniper that got me. It went right through the left arm (the upper part, right in line with my heart), tore my shirt pocket and slit up my fourth finger in the right hand. It was the second marvellous escape I had. They bandaged it up and sent me aboard the Gloucester Castle, which was a sort of hospital ship.

When we had 700 wounded on board we sailed for Alexandria, which we reached last Sunday. On Monday we entrained in the hospital train for Cairo the worst cases being kept in Alexandria. The Red Cross motors were waiting for us and they took us away to the hospital. Most of the hospitals are full up here and they are very busy. The Cairo ladies–English and French–have offered their services and are doing great work here, helping the trained nurses. They are very nice, too . . . I want to get back again, though, and march into Constantinople with the boys

James was a robust young man who recovered and returned to Anzac just three weeks later and remained until just before the evacuation.

As was often the case, letters home from servicemen often gave a glimpse of how other servicemen from their hometown also fared on the battlefields. Private Wally Sutherland, another Mildura boy, had mentioned in his letter to his father…” I am still going strong after several weeks in the trenches. Tom Carpenter is with me, he has been through the whole lot and has only a few scratches…….. Things are very quiet here this last few days, but no one knows how long it will last. I was having a talk to Jim Hamilton, who is back again and looking splendid. He is sapping on our left , at Courtneys Post”

It must have been some relief for Jim’s parents to read that their son was “looking splendid”

James continued to serve at Gallipoli up to the 11th November 1915 when the 1st FCE was finally relieved and sent for a brief spell to Lemnos Isl. after the company had spent 201 days on the peninsular. Shortly after, the Gallipoli campaign was over, and the peninsula was evacuated.

After a spell at Lemnos Isl. James and the men of the 1st FCE left the island and returned to Alexandria, Egypt on the troopship ‘Caledonia’, arriving on the 27th December 1915.

In January 1916, James was promoted to Lance Corporal, then on March 21st, left Alexandria on the Invernia and proceeded to the front lines in France. The day before, he was promoted to 2/Corporal. The 1st FCE deployed to the relatively quiet trenches near Armentieres in what was known as the ‘Nursery Sector’, the trenches where troops were quickly schooled in the routines of trench life on the Western Front. In July, the unit moved south with the infantry to support them in the battles at Pozieres and Mouquet Farm on the Somme.

Battle of Pozieres

The village of Pozières is located in the Somme Valley, France. The main road running along the ridge, in the middle of the British sector of the Somme battlefields, ran from the towns of Albert to Bapaume and close by stood the village of Pozieres, the highest point on the battlefield.

On the 19th July 1916 the men of the 1st Field Company Engineers had bivouacked just outside of Albert, approximately 3 miles from the front lines. On the 21st July they marched into Albert and commenced helping to dig a communications trench that same night. The heavy bombardments from the Germans had already commenced and were relentless.

By Sunday the 23rd July the company had moved in closer to the front lines at Pozieres and commenced construction of a strong point for a machine gun placement. Original 233 Cpl Thomas Arkinstall reported that the section was in front of Pozieres about 100 yards past the village, and were digging an advanced Machine Gun position overlooking two roads leading to Pozieres and Bapaume.

For four days, Pozieres would be pure hell for the men of the 1st Field Company Engineers.

Pozieres Main street 1916

The drawings above from the unit diaries show the detailed plans for the construction of the “Strong Point” and machine gun placement. Original 29 Bob Lundy recorded in his diary on the 23rd of July the casualties and the devastation of the day, noting that there were dead lying all along the track and every inch of ground was just shell holes.

Within the first four days of the operations, the return lists for the engineers were prepared by original Lieut. Robert Osborne Earle for Major Richard Dyer outlined the devastation to the men of the 1st Field Company.

The casualties list recorded the men who were either killed, wounded, missing, gassed or suffering shell shock, between the 22nd and 26th July 1916.

James Hamilton was on the large list of casualties sustained by the 1st FCE. James, wounded in the left buttock by a gunshot, was hospitalised and transported to England for surgery and to convalesce and spent the next six months recovering from his wounds. Fully recovered, James returned to his company which was still active in the field on the Western front and reported to his O.C. on the 23rd February 1917 and was later promoted to Corporal, vice to 65 Edward Makinson in May 1917. His unit was in the freezing Somme Valley, working on road and rail repairs behind the lines and improving the defences in the front lines. In the spring of 1917, the 1st FCE joined the operations northeast of Bapaume, repairing roads and bridges destroyed by the enemy as they retreated to the Hindenburg Line, their new defensive position. When the British military focus shifted to Ypres in Belgium, James and 1st FCE unit moved north to prepare for the new campaign. On 20 September 1917, the 1st and 2nd Divisions advanced in the centre of the assault along the axis of the Menin Road, east of Ypres.

At 5.30 am on the morning of 20th September 1917, the Battle of Menin Road kicked off with the 1st FCE soon in the thick of it. A detailed report of the operations on the 20th and 21st of September 1917 is attached to the War Diary. (This Link to the PDF is available to read highlighted below).

WAR Diary AWM4 1st Field Company Australian Engineers – September 1917 ( RCDIG1008697)

Lieut. Hugh Lyddon originally with the 2nd FCE was now attached to the 1st FCE and was in charge of No.1 section to which James Hamilton was attached. Lieut Lyddon’s report briefly described how his section was moved up to an area known as Hooge Crater, and then set about the respective tasks of helping construct a number of strong points and a communications trench. On the morning of the 21st September, enemy bombardments commenced at 4.30 am, and at daylight, enemy balloons enfiladed the trenches, and enemy field guns were turned on them. Sniping continued throughout the day and then late in the afternoon, at 4.30 pm, the enemy shelling intensified and continued without pause until 8.45 pm. It was reported that most of the tasks had been achieved, and in addition, there was special mention of the work by original sappers 196 Frederick Meads, 167 2nd Cpl Albert Currie, and 43 Sgt Arthur Baldwin.

At this point, there were no accurate details on the casualties sustained during the day, and both 43 Arthur Baldwin and 76 James Hamilton were reported missing and believed killed. It was not until the following morning, when O.C Major Dyer inspected the area and confirmed the bad news, that James Hamilton and Arthur Baldwin had been killed in action.

It was later confirmed by original sapper 196 Fred Meads, both Cpl. James Hamilton and Sgt Arthur Baldwin were consolidating the position at a place known as Lone House, Hooge, widening and deepening a sap from the supports to the front line which ran through the ruins of an old house. They were“At Polygon Wood about dusk and consolidating the trenches ….. Baldwin and Hamilton were in a hole together when a shell came over and hit them directly.” – Meads

Original sapper 242 Thomas Cook was a witness to their death and gave his account. He was a reliable witness, familiar with James’s family background and also having earned himself a Military Medal for his work that day. Thomas gave his horrific account of collecting the body parts and helping bury the remains. He also describes how he was in charge of making the cross, and sapper Dixon had made a centrepiece, an image of Australia. He reported “that he was a big tall strapping young fellow” about 21 and the only son in the family.

Sapper Frank Slee’s accounts were equally as graphic as the other witnesses. Frank Slee knew James Hamilton well and stated he had a sister, nursing in one of the hospitals in Rouen, France. He confirmed that James Hamilton was buried at Lone House about 50 yards off the centre of Polygon Wood.

In local news back in James’s hometown of Mildura, ‘The Mildura Cultivator’ on Wednesday, the 17th of October, reported the worrying news that James’s parents had received early reports of him missing in action.

“After over three years’ service “Jimmy” Hamilton is reported as having been missing since the 21st September. It is hoped that the next news received of him will be better news. ‘Jimmy” is the only son of Mr Jas. A. Hamilton, Merbein, and Nurse Hamilton, Mildura. His sister Daisy, by the way, is on the way back from Europe.”- reported by Steele Blade

“Steele Blade” in his regular column, ‘Chiefly of the Mallee” was actually noted personality Samuel Gifford Hall who had a close relationship too James and his family. He was a big supporter of the boys from the Mallee and was desperately hopeful that “Jimmy” was alive.

“Among the latest reports of happenings to local boys at the war front is the news that Private “Jimmy” Hamilton, son of Nurse Hamilton and Mr James Hamilton is “missing.” The writer has known stalwart 6-foot “Jimmy” Hamilton since the latter was a wee laddie in knickerbockers and has watched him develop to the magnificent manhood evidenced in his letters to his mother-such letters as stamp him indeed one of those whom Will Ogilvie has immortalised as “the bravest thing God ever made.” And now, after three years -Gallipoli- France – “Jimmy” is missing. Words are cheap, futile, but let us not only hope for the best but believe the best, that he has not made the supreme sacrifice, that he will come back to us to take honored place in the land of his birth. Those letters to his mother if one had a son of one’s own who could write such one would feel one had not lived in vain. Wherever he is, alive or dead in the flesh, let me record that in him dwelt the soul of a man. It perhaps is not meet at this time to say what is in one’s heart, but if Young Australia at large had done its duty “Jimmy” would not be missing. He would ere this have been relieved from the duty that held him so long. But whether alive or “dead” (such as he do not really die), let his folk take pride in him, pride indeed. Jimmy Hamilton-man, though merely boy in age.” – “Steele Blade”

10 days later, the tragic news of ‘Jimmy’ Hamilton’s death had reached his parents, and the devastating news was published by “Steele Blade” in his local news column.

“Corporal “Jimmy” Hamilton, who was recently reported as missing, is now recorded as killed. Though not yet 21 years of age, “Jimmy” had seen over three years of active service. He was always a good lad and he grew up to be a very fine man. Undoubtedly he has qualified for citizenship in the Eternal country where, by and by, he will give a hearty welcome to his dearly beloved parents and sisters, never to be parted again. Though the time of anticipated re-union is postponed it will be all the more sweet when it is consummated in the Great Beyond. “It is well with the lad”

A few days later Steele Blade made a touching tribute to “Jimmy”

“Starting my columns this morning-Monday–With a bit of smart in my eyes and my tobacco tasting far from as sweet as usual, the first thing I feel I must write is an In Memoriam line or two to my young friend, James Morrison Hamilton, killed in action in France after three years’ cheerful and faithful service in the cause of humanity. Yesterday a bit of verse was running through my head, today some thing is lodged in my heart. The very highest In Memoriam tribute to “Boy Jimmy” (as I shall ever remember him, though in very truth he was man) is to say: Would God, Boy Jimmy, I had been granted a son such as you to represent me in the ranks of the faithful. You were not only a splendid soldier, but a splendid son, and a cherished friend, and though your clay be “dead,” your spirit will ever be with us. Rest, son of your mother and the Empire, from your long task until the great Day of Reunion.

There is no known grave for James Hamilton. However, The Menin Gate Memorial, so named because the road led to the town of Menin, was constructed on the site of the gateway in the eastern walls of the old Flemish town of Ypres, Belgium where hundreds of thousands of allied troops passed on their way to the front, the Ypres salient, the site from April 1915 to the end of the war of some of the fiercest fighting of the war.

The Memorial was conceived as a monument to the 350,000 men of the British Empire who fought in the campaign. Inside the arch, on tablets of Portland stone, are inscribed the names of 56,000 men, including the 6178 Australians, who have no known grave. James Hamilton appears on Addenda Panel 57.

Copyright ©VanceKelly 2019

SOURCES and ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

PHOTO OF JAMES – Courtesy of The Hamilton Family

AWM, NAA, NLA, ANCESTRY.COM

AWM – Men of Menin – by Robert Scott

Scott Wilson – fellow researcher

NOTES:

When his personal effects were returned to his mother in Mildura, it included a diary, a book of poems, a bible, a fountain pen, letters, photos and cards.

After the war, Margaret Daisy Hamilton married original 96 Hugh Stewart GEDDES – perhaps they met in France, or perhaps Hugh personally delivered the dreadful news of James Hamilton’s fate to Margaret.